(Editor’s note: This is a slightly longer version of the Default Lines column from the Nov./Dec. issue of eSchool News.)

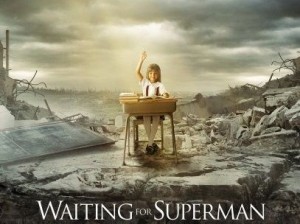

As a strong supporter of American public education, I don’t know what’s more depressing: that the film Waiting for ‘Superman’ is so bad, or that so many critics have heaped such high praise upon it. But—given our propensity for solutions to complex problems that can fit neatly on a bumper sticker, in a pull quote, or in a seven-second sound bite—I guess I shouldn’t be surprised.

I realize that saying you support public education these days is like saying you support Mel Gibson, or you like the French. But it’s about time someone stood on a rooftop and shouted through the cacophony of ill-informed opinions that no other nation in the world tries to do so much—prepare all children for college or the workforce, regardless of their background, circumstances, or special needs—in the face of so many challenges. Yes, we can do better—we must do better—but given the daunting nature of these challenges, it’s a wonder our schools are doing as well as they are.

If you’re a teacher, you know these challenges all too well: Children coming to school malnourished, or not ready to learn … Kids who have learning disabilities, or who don’t even speak English … Classrooms packed with 30 or more students, yet lacking the fundamental resources necessary to give all children the individual attention they deserve … Cell phones, TV, and video games that divert students’ focus from the lessons at hand … Parents who don’t make their children do homework, or who excuse their poor behavior … Overloaded schedules that leave far too little time to plan engaging lessons, collaborate with colleagues, or advance one’s own learning … the list goes on.

It’s too bad filmmaker Davis Guggenheim fails to grasp any of these challenges.

Remarkably, in a documentary spanning nearly two hours, Guggenheim doesn’t interview a single classroom teacher about what’s wrong with American public education. The only appearance in the film of someone representing a teacher’s perspective is Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, and let’s be honest: She’s on screen merely to act as a foil, not to offer any wisdom.

(In a textbook example of the propaganda technique known as “stacking the deck,” each time Weingarten gets screen time in the film, Guggenheim cuts her off after she makes a single statement, without allowing any follow-up explanation that would add necessary context to her remarks. The result, if you’ve seen the film in a public theater, is exactly the kind of audible gasp from the audience that Guggenheim is aiming for.)

Other than that, the so-called “experts” interviewed in the film are all education outsiders—Newsweek’s Jonathan Alter, Microsoft’s Bill Gates—and controversial school reformers like Geoffrey Canada and Michelle Rhee. What emerges from these interviews is a reinforcing of tired, old stereotypes about how unions are blocking much-needed reforms … but very little new insight.

We are told, for instance, that once teachers get tenure, they are virtually impossible to fire—and if we just got rid of the bottom 6 percent of teachers, we’d be doing as well as Finland in international comparisons.

It sounds so simple, doesn’t it? Fire the worst teachers, and watch our students’ test scores magically rise. But where are those new teachers going to come from? Will they be given the same training, mentoring, resources, and support as the teachers they’re replacing—which, in most cases, is not nearly enough? And if so, why would we expect a different result?

By presenting unions as “a menace and an impediment to reform” (a direct quote from the film), Guggenheim creates the kind of two-dimensional villain that you’d expect to find in a comic book featuring the hero mentioned in his film title. And he focuses on this caricature at the expense of other, very legitimate problems in public education.

The trouble with the “fire the bad teachers” mindset is that it assumes teachers work in a vacuum, and that they’re solely responsible for their students’ outcomes. In reality, students are in school for only 25 percent of their day, so their development depends on many factors outside a teacher’s control. And teachers, in turn, are largely dependent on the support structures they get from school and district administrators.

Are there some poor teachers who don’t put forth much effort? Yes, just as in any other field—and these individuals have no place in a classroom. But the vast majority of teachers—even those whose students’ test scores might suggest they are “ineffective”—are trying hard, and they want to be successful. They have an incredibly difficult job, and they need more support to be effective. Firing these individuals and hiring new teachers in their place is no guarantee of success—and it ignores the underlying problems that led to mediocrity in the first place.

If Superman’s contributors thought highly enough of teachers to listen to their concerns, they’d learn that teachers are crying out for more support. In fact, teachers would rather have this support than higher salaries.

In one of the largest-ever national surveys of public school teachers, commissioned by Scholastic Inc. and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and released in March, fewer than half of the teachers surveyed (45 percent) said higher salaries are absolutely essential for retaining good teachers. More teachers said it’s essential to have supportive leadership (68 percent), time to collaborate (54 percent), and high-quality curriculum (49 percent).

This is why merit pay won’t work: It assumes teachers would just try harder for the promise of more money. But most teachers already are trying as hard as they can. What they need instead is more help—such as training on ways to better identify their students’ individual needs and tailor their instruction accordingly, time to plan collaborative projects that would stimulate their students’ interest and lead to higher-order thinking skills, and the technology tools that would allow them to adopt these techniques. Not surprisingly, a new study from Vanderbilt University, which found that merit pay had no impact on student test scores, appears to support this notion.

Yet, merit pay is one of several trendy education reforms that Superman embraces uncritically. The AFT and other education groups have legitimate concerns about many of these reforms, as we’ve written about before. (See here, here, here, and here.) But nowhere in the film do viewers learn what those concerns are—and so the dialogue that Superman purports to want to start about improving U.S. education can’t even get off the ground.

The film alludes to several charter schools as models for reform, such as the Harlem Children’s Zone schools that Canada leads in New York City. And in a haunting final sequence, we see the very public anguish of several families as their children are denied placement in these various schools through an arbitrary lottery process. But what is it about these schools that makes them successful? That’s what the film really should have focused on—and it would have been far more instructive if it had.

The key to these schools’ success cannot be summed up as freedom from the constraints of union rules, as Guggenheim would have us believe. For if that were the case, then charter schools would be outperforming traditional public schools across the board. In truth, charter schools do no better, on average, than regular public schools do. There are some exemplary charters, just as there are exemplary public schools—and there are many bad ones, too.

If the film had looked more closely, it would have discovered that the elements that make some charter schools a success are the same factors that lead to success in traditional public schools: strong leadership; a vision for ensuring that all students can succeed, and a plan for addressing each child’s unique learning needs; a challenging and engaging curriculum that is relevant to students’ lives and interests; and committed teachers who have the training and the tools they need to realize this vision.

New York City’s School of One, for instance, is a charter school whose success relies on giving each child an individual learning plan in math. And the schools we profile in our Special Report on blended learning—a mix of traditional schools and charters—are using a combination of face-to-face and online instruction to personalize the curriculum for students, while also giving them the in-person support that will help them thrive.

If we really want to have an honest conversation about the problems facing U.S. public education, then we also need to address the issue of funding in a more responsible way.

We learn from the film that average spending per pupil has more than doubled since 1971, from $4,300 (in inflation-adjusted dollars) to $9,000. Doubling the amount of money we’re spending on education might be worth it, Guggenheim says in his voice-over narration, “if we were producing better results—but we’re not.” He goes on to show how average scores on reading and math achievement tests haven’t really increased during this time.

What’s missing from this indictment is any historical perspective for understanding why. As it turns out, there’s a pretty reasonable explanation—and much of it has to do with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

In 1971, there was no law requiring schools to teach students with special needs. Before IDEA’s predecessor statute, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, was enacted in 1975, U.S. public schools were educating only about 1 in 5 children with disabilities, according to the U.S. Department of Education. But that changed with the new legislation, and in 2006 more than 6 million children were receiving special-education services under IDEA.

What’s more, despite promises by the federal government to cover up to two-fifths of the cost of providing these services, local school systems generally are left footing more than 80 percent of the bill themselves.

Compounding the challenges facing our schools has been an explosion in the number of students who are English-language learners during this same period. Between 1979 and 2008, the number of school-age children (ages 5-17) who spoke a language other than English at home increased from 3.8 to 10.9 million, or from 9 to 21 percent of the population in this age range, according to federal officials.

Think that could help explain why we’ve doubled our investment in education over the last 40 years, with apparently little to show for it?

(Actually, if you consider that schools today are teaching many more students with special needs and who speak English as a second language, the fact that average test scores haven’t declined over this period probably should be a cause for celebration, not rebuke.)

Let’s also be honest about how much it costs to attain success. At least two of the charter school projects featured in Superman, Locke High School in Los Angeles and the Harlem Children’s Zone, get much of their funding from private or corporate contributions—another detail the film conveniently omits.

The Harlem Children’s Zone serves thousands of families in a 100-block area of New York City—but it does so with an $84 million budget. At Locke, two years after a charter group assumed control of the school, gang violence is down, fewer students are dropping out, and test scores are on the rise—but it’s taking an estimated $15 million over four years to achieve this turnaround, according to the New York Times.

Give credit to Guggenheim for shining a national spotlight on the need to improve U.S. public education. But it’s time we had a deeper, more meaningful, and far more introspective conversation about this topic—one that moves well beyond the bland banalities found in Waiting for ‘Superman.’

Do we want to continue trying to prepare every child for college or the workplace, regardless of that child’s needs or circumstances? If so, then how can we achieve this goal … while simultaneously raising our standards and regaining our status as a world leader in student achievement?

These two complementary challenges are not outside our reach—but it will take a much bigger investment in public education than we’ve made to date, as well as an approach that eschews flash over substance.

At eSchool News Online, we’ve created a platform for holding this important conversation: www.eschoolnews.com/reform. This brand-new section of our web site contains the latest news, research, and opinions to help school and community leaders explore real, effective strategies for moving education forward in the 21st century.

The challenges facing public education today require responsible, thoughtful, multifaceted solutions that involve all stakeholders working in concert—not shallow responses or agenda-driven reformers with superhero aspirations. We don’t need a Superman; what we need instead is a collective commitment to doing the hard work necessary to bolster public education as the foundation of a strong democracy. Anything less would be a disservice to our nation and our children.

- Can technology help schools prevent AI-based cheating? - April 14, 2023

- How to ensure digital equity in online testing - July 6, 2022

- ‘Digital skills gap’ threatens innovation - May 30, 2022

Comments are closed.