No. 5 on our list of key ed-tech trends for the new school year is the proliferation of maker spaces in schools

[Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of stories examining five key ed-tech developments to watch for the 2014-15 school year. Our countdown continues tomorrow with No. 4.]

During a special summer camp last month, the Economic Development Center at West Virginia State University was buzzing with activity.

High school students Drew Jett and Christian Rohr were sitting in front of a computer, designing a silencer for paintball guns. Fellow student Sully Steele sat nearby, working on a prototype for an arm brace that holds a smart phone on the user’s sleeve until it’s needed—flip your wrist, and the phone slides into your hand. Not just intended as a cool, spy-type gadget, the device was meant to protect users’ pelvic regions from the electromagnetic radiation emitted by their phones.

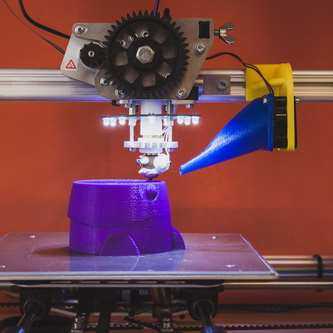

All three students were using the free, three-dimensional modeling software Sketchup Make to design their creations, and they planned on using a 3D printer to bring their creations to life.

Paintball guns are “quite loud and obnoxious,” Jett said. “So we’re going to try and make [them] a lot more silent. There are no silencers currently for paintball.”

The students’ ideas were just the kind of innovative thinking the DigiSo Maker Camp’s organizers were hoping to foster.

“We touch on a little bit of design thinking, entrepreneurship, problem solving,” said instructor Venu Menon. “And then we … give students a lot of leeway to be able to use [technology] to create a project.”

The DigiSo Maker Camp is an example of how the “maker movement” is catching on quickly in education. As the new school year approaches, “maker spaces” are cropping up in countless schools and libraries nationwide.

Having students complete hands-on projects isn’t new. For years, many educators have championed a constructivist, learning-by-doing approach in schools.

But now, a number of factors have converged to push this concept into the education mainstream.

(Next page: Why the maker movement has grown in popularity—and how it helps meet a critical need)

For one thing, rapid advances in technology have allowed students to create much more complex projects, with less specialized knowledge, than previous generations could create.

Tools like Scratch, littleBits, and MaKey MaKey give students the ability to design and innovate without having to be experts in computer programming or electrical engineering, said Trevor Shaw, director of technology at the Dwight-Englewood School in New Jersey.

Scratch is a free programming language that lets students create their own interactive stories, games, and animations, simply by dragging and dropping blocks of commands. littleBits allow students to create electronic devices without having to wire or solder pieces together. MaKey MaKey is an “invention kit” that turns almost any object into an input device.

What’s more, 3D printers are becoming cheaper and more accessible for schools, opening up further possibilities for creation. This rapid technological shift “is a real game changer,” Shaw said. “It’s so far out of the realm of what we could have imagined five or six years ago”—and it has had a profound effect on the maker movement.

The rise in the maker movement also coincides with a national focus on bolstering science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education to prepare students for the jobs of the future, which will rely heavily on innovation. Schools are using hands-on projects to make STEM subjects more relevant and engaging for their students.

In June, President Barack Obama hosted the first White House Maker Faire, where 30 “makers” gathered at the White House for a day to share their interests and explain why creating is important to them.

“The rise of the maker movement represents a huge opportunity for the United States,” the White House said. “America has always been a nation of tinkerers, inventors, and entrepreneurs.”

Dale Daughterty—creator of Maker Faire and founder of Make magazine, which helped launch the current maker movement—was a speaker at the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) annual conference in Atlanta in June.

“Kids don’t understand why you want them to take science or math,” Daugherty said during the conference. “Making is a door that they will walk through on their own.”

At Dwight-Englewood School, an independent, coeducational day school with just under 1,000 students, officials are designing a new STEM facility that will include spaces for students to create. Shaw believes the biggest value in these maker spaces is teaching students how to become effective problem solvers.

“Giving kids the opportunity to hold a tool and go through the process of struggling a bit to get it to work—that connects with learning pretty deeply,” he said. “A lot of times, we train students how to get the ‘right’ answer—but things don’t always work perfectly in the real world. Being able to overcome that is a key skill.”

He added: “I love that we’re giving kids the opportunity to innovate and figure things out for themselves—it helps them develop the resiliency they’ll need to succeed.”

Material from the Charleston Gazette and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram was used in this report. (c) 2014; distributed by MCT Information Services.

- ‘Buyer’s remorse’ dogging Common Core rollout - October 30, 2014

- Calif. law targets social media monitoring of students - October 2, 2014

- Elementary world language instruction - September 25, 2014