I was really intimidated when I first heard about design thinking. I also had a lot of questions: What is design thinking? Isn’t it just for techies? How is this relevant to my elementary school-level classroom?

The epicenter of design thinking is the d.School at Stanford. According to the d.School, “… design thinking is a methodology for creative problem solving. You can use it to inform your own teaching practice, or you can teach it to your students as a framework for real-world projects.” Founded in 2004 by a few Stanford professors including faculty director David Kelley, the d.School offers courses to all students at Stanford, no matter their major. They also have made their approach available to a variety of industries, including education.

Schools often assume that design thinking is a “techie thing” and send their edtech coordinators and directors to design-thinking workshops. Although design thinking has been adopted widely by the tech industry, its approach can be applied by any organization that wants to adopt a way to solve problems empathetically and collaboratively. In schools, design thinking complements inquiry- and project-based approaches to teaching and learning.

I had the privilege of attending a couple of deep dives into design thinking at Stanford’s d.School. When I attend workshops, I’m always thinking of ways to bring back what I’ve learned and make it relevant to my colleagues and students. My aha moment came when I realized that, like the scientific method, design thinking is just another inquiry cycle that guides students by giving them steps to conduct research. Design thinking is a social-scientific approach to solving human-centered problems. Its main driver is empathy, a skill you can build and foster in your classroom.

The inquiry cycle

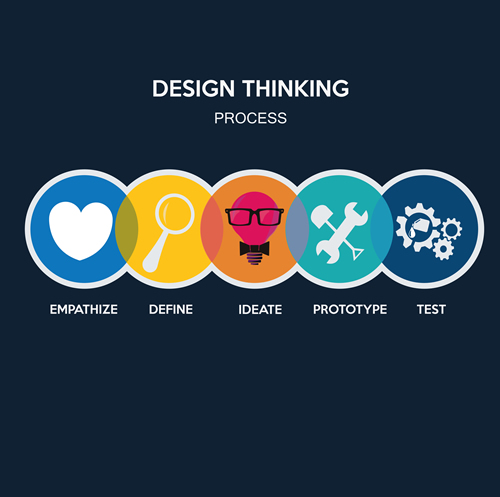

If you’re like me, the steps of the scientific method have been thoroughly imprinted on your brain since middle school. Like the scientific method, design thinking has discrete steps that guide students through the inquiry cycle.

Empathize: Choose one topic and ask lots of questions. What’s your least favorite chore? What don’t you like about it? How does it make you feel? Dig deeper with why questions: Why does it matter to you? Why do you do it?

Define: Now that you’ve empathized deeply, what information stands out? What is the person struggling most with, and how can they accomplish their goal?

Ideate: What type of solution do you want to offer that person? A tech product? A script? A plan?

Prototype: What can you create for this person that will meet their needs?

Test: Go back to the person and ask them to test it out. Does it meet their needs?

(Source: Stanford d.School)

Now, let me break it down so you can see how it aligns with an inquiry cycle you’re already familiar with. I’ve included concrete examples and student artifacts to help you draw connections to your own teaching.

Step 1: Empathize.

When you make observations and ask questions using the scientific method, you are empathizing, which is the first step in the design-thinking cycle. In design thinking, empathizing with the person you’re helping requires you to ask questions to better understand the issue you’re attempting to solve. Empathizing helps us practice how to ask questions and engage each other in meaningful conversation without judgment.

A group of my second-graders wanted to explore the topic of deforestation. They started by writing questions so they could focus their inquiry and dig deeper. They asked, Who is deforestation affecting? Why do people cut down trees? How can people protect them? What happens when all the trees are cut?

Then, they used Post-it notes to document answers to their questions that they found in books and through interviews. This was a great opportunity to talk about primary and secondary sources of information as well as to practice asking questions without judgment.

Step 2: Define.

Once students collect the information (empathize), they move on to defining the issue. This is similar to a hypothesis in the scientific method. In design thinking, defining the issue means that you’re finding some strong trends in the information to make a “needs statement.” The information is showing you a strong need, and the statement will help students focus on a specific issue to solve for a person. Check out this second-grader’s needs statement:

“Racist person needs a way to mend their relationships to build a community with equal rights.”

Notice the verbs “mend” and “build.” It’s really important that the needs statement is actionable. Verbs are a key component to writing a needs statement.

Steps 3 and 4: Ideate and Prototype.

After students zero in on a specific “need,” they begin the ideating and prototyping phases. Similar to testing your prediction in the scientific method, this is when they create models to meet the need identified in the needs statement. In these phases, it’s important to give students a range of tools to get creative, such as a variety of paper, pens, recycled materials, tape, ribbon, and so on. The prototype can be anything from a drawing, a script for a play, a how-to manual, or a Lego model.

Design thinking allows students to use their imagination in creative ways. Students empathize deeply with someone they know or an issue they’re passionate about. As a result, your students are motivated to communicate, collaborate, plan, write, and revise.

Step 5: Test.

Finally, students test by connecting back to their user to get feedback on their prototype. During this phase, we practice how to receive feedback. We talk about not getting defensive, being open to suggestions, and asking more questions. This phase connects back to our discussion on empathy, which is the central driver of design thinking.

Give it a try!

My fellow teachers, please don’t be intimidated by design thinking. If you’re familiar with the scientific method, you can integrate this cycle into your teaching. It’s collaborative and empathetic and challenges the designer to listen carefully to another person’s needs. Listening with empathy is central to the process, and I strongly believe it’s a skill that is transferable to any situation.

You may want to use it with your students to redesign their homework experience or their seating arrangements, solve issues on the playground, or negotiate responsibilities in the classroom. Have a look at this Virtual Crash Course Playbook provided by the d.School to help guide you through the cycle. Design thinking is an inquiry cycle that can help students dive deeper into our relationships with each other, foster deep empathy in our classrooms, and, ideally, lead to real change in our lives and communities.

![]() [Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on Common Sense Education.]

[Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on Common Sense Education.]

- 3 ways to avoid summer learning loss - April 19, 2024

- High school students say AI will change the workforce - April 18, 2024

- Motivating students using the Self-Determination Theory - April 17, 2024