The leap from elementary school to middle school can be daunting, particularly for students who struggle academically. Each day, students working below grade level not only toil to keep up with their classmates, but to retain their confidence. Every reading passage or math problem they don’t understand creates frustration and anxiety, and chips away at their resolve to stay in school.

Research shows that ninth grade is a bottleneck for many students who find their academic skills insufficient for high school work. One reason the ninth grade finishes off so many students is that many of them have already been struggling and disengaging for three years or more before entering high school (Balfanz and Letgers 2006).

As such, the challenges facing middle school educators are significant. How do we fill in learning gaps while maintaining a consistent focus on grade level standards? How do we engage struggling learners who tune out during remedial instruction? How do we help students journey through middle school with their self-confidence intact?

As principal of Bell Street Middle School in the Laurens County School District in Clinton, S.C., I posed these questions to our school leadership team. We researched answers to these questions and discovered they could be found in individualization, motivation, and accountability. To help close the achievement gap, we adjusted students’ schedules to allow for a double-dose of instruction in English/language arts and mathematics, and we tailored learning to address each student’s needs. We created an incentive program to recognize students for their hard work. We also provided tools to help students become more accountable for their behavior.

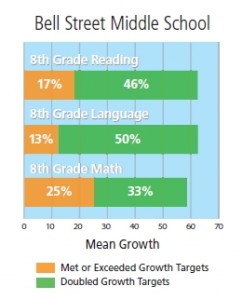

Since taking a more personalized, positive and, proactive approach, Bell Street Middle School has helped struggling learners achieve gains on the Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) tests, with many students more than doubling expected growth targets. We have decreased failure and retention rates. We have also reduced discipline incidents and suspensions. Through these efforts, we have improved students’ self-confidence and their desire to succeed.

Recognizing what doesn’t work

Bell Street Middle School enrolls approximately 680 students in grades six through eight. Seventy percent of students receive free and reduced lunch. At the beginning of 2007, we were struggling with state test scores. While many students were scoring at the Below Basic level, we knew the level of instruction in the classroom could not drop because we needed to stay focused on grade-level standards. There was a need for remediation on a regular basis.

To help our students, we initiated a homework tutoring program after school with little success. There were a few reasons this approach did not work. First, while the program allowed teachers to work with students on specific skills, it focused primarily on grade-level curriculum rather than basic skills students may have missed. Second, the after-school program was offered at the same time as many other extracurricular activities. Third, at the end of the day, students were not motivated to stay and do more of the same type of work.

Thinking technology could help, we tried a couple different software programs but found they were too limited. We also implemented software that was supposed to differentiate instruction using students’ MAP scores. This prescriptive instruction, however, was not automatic and the process proved to be too time consuming for teachers.

Thinking more instruction would help, we assigned students to a 45-minute class for remedial math or reading. This was in addition to students’ regular 90-minute math or reading block. While the class sizes were small, the instruction was mainly teacher-led and resources were limited to textbooks and other books. Although teachers did their best, students were tuning out. After 90 minutes of instruction in their regular block, the last thing students wanted was another 45 minutes delivered in the same manner.

Individualizing instruction

In 2007, I had an opportunity to review a software program our school district was considering to address our students’ academic needs. Our leadership team decided that the program fit our needs and developed a plan for implementation. That fall, Bell Street Middle School implemented a software program called Classworks, which includes 17,000 instructional activities drawn from 265 software titles, and it allows for individualization of instruction.

We first began using the software with seventh and eighth grade students identified at the Below Basic level in language arts and mathematics on the South Carolina Palmetto Achievement Challenge Test (PACT). As part of their daily schedule, students visit the Classworks Lab for one 45-minute period, in place of one of their two elective classes. Students work on language arts one day and math the next, alternating each day.

We quickly saw a key benefit in that the software automatically builds a program around each child’s needs, based on the South Carolina state standards, to help each child move to the next level. This is crucial at the middle school level, where a teacher may teach 100 students throughout the day. If a teacher has students who are behind in reading and math, it is difficult to carve out time to address their needs. By adding individualized instruction during an additional class period, we can provide remediation without sacrificing regular class time spent on grade-level standards. We also import students’ MAP scores into Classworks, which automatically creates individualized learning paths for each student, based on his or her own scores.

Further, because the software offers interactive instruction through a multi-sensory approach–including voice, pop-up text, audio support, video, photographs, artist drawings, and animated clips–students are engaged. With different activities from different publishers, students can encounter a subject from varied perspectives and learning styles, which helps to keep their attention.

In 2009, we expanded our implementation to include sixth graders identified as needing extra help, based upon their fall 2008 MAP scores.

Using the software’s reporting system, lab manager George Goings regularly monitors students’ progress. Looking at the data, he can easily determine if students are engaged or just going through the motions. If a student is not applying himself, he and the student discuss how to get back on track.

Motivating students every day

To motivate students to work hard every day, Bell Street Middle School implements an incentive program with rewards for students who score 90 percent or higher on a selected number of lessons in the software. The incentives help students become more goal-oriented and recognize them for academic achievement. Many of these students have never been recognized for academic accomplishments. This recognition is rewarding to the students and their families.

On a monthly basis, Goings runs a report that details the number of units each student has mastered in the software. Student progress is charted on class spreadsheets that are displayed on bulletin boards in the lab and hall. After mastering a selected number of lessons, students are eligible for prizes such as restaurant gift certificates, ear buds, T-shirts, and a year-end drawing for MP3 players.

Incentive distribution days are a big hit with students. Several of these days are filmed by the school news crew and shown during the morning homeroom broadcast. As a result, students receive praise for their accomplishments from their classmates and students and teachers across the school.

Achieving gains

This incentive program has been a success in that it has students scoring higher on their MAP tests. In fact, some students did so much better they were able to choose another elective in place of Classworks Lab for the next semester.

In English/language arts in grades six through eight, 75 percent of students increased their MAP test scores from fall to spring by 5 points or more, 39 percent increased by 10 points or more, 13 percent increased by 15 points or more, and 4 percent increased by 20 points or more.

Several students met their MAP on-grade level expected growth targets in every grade and subject; some for the first time. In many cases, students’ growth more than doubled the expected growth targets. In eighth grade, for example, more than one-third of students doubled their expected growth targets in every subject.

Students’ MAP gains were also evident in fall 2008 PACT scores, as the number of seventh graders performing Below Basic dropped from 45 percent to 36 percent in English language arts, and from 32 percent to 27 percent in math.

In addition, from fall 2008 to spring 2009, the number of Classworks students in jeopardy of failing one or more subjects dropped from 40 students to less than 10. From 2007-08 to 2008-09, the number of students retained school-wide plummeted from 50 students to five students in grades six through eight.

Holding students accountable for their behavior

To extend student accountability, we also implemented Time to Teach, a program that focuses on strategies for teaching children how to be responsible for their own behavior and learning. At its foundation is the notion of “teach-to’s,” which are behaviors and routines teachers purposely and clearly teach every student for the classroom to run smoothly. Through this program, our teachers teach positive, explicit behaviors for everything that happens in school–from how to ask a question in class, to how to sharpen a pencil, to how to ask to use the restroom.

As a result, student behavior has improved dramatically. From 2007-08 to 2008-09, discipline referrals were reduced by 43 percent and suspensions were reduced by 67 percent.

Building student success

At Bell Street Middle School, there is great teaching taking place by very dedicated and hard working teachers. The integration of individualized instruction, along with the practice of holding students accountable for their learning and behavior, has also contributed greatly to students’ achievements. Students are proud of their accomplishments and are working diligently to meet their academic growth goals. Through the innovative strategies of the school leadership team, Bell Street Middle School is smoothing the transition from elementary to middle school and preparing our students to be confident, successful learners.

References:

Balfanz, Robert and Nettie Letgers. 2006. Closing “Dropout Factories”: The Graduation Rate Crisis We Know and What Can Be Done About It. Commentary in Education Week 25, no. 42.

Maureen Tiller is the former principal of Bell Street Middle School and now serves as the district’s executive director of instruction K-12.

- Friday 5: Virtual field trips - April 26, 2024

- Google, MIT RAISE launch no-cost AI training course for teachers - April 26, 2024

- 4 ways to support work-based learning - April 23, 2024